Meet Meredith Sadoulet, The Arc’s National Board President

If you’ve been following The Arc’s work this year, you’ve already felt Meredith Sadoulet’s steady influence. She stepped into the role of Board President in January, and while she’s not new to the job anymore, many in our community may still be getting to know her. Meredith is thoughtful, values-driven, and deeply committed to creating a future where disability doesn’t limit opportunity. She’s a member of the disability community herself, a family member to people with disabilities, and a professional with years of experience leading workforce strategy and inclusion at Fortune 100 companies.

If you’ve been following The Arc’s work this year, you’ve already felt Meredith Sadoulet’s steady influence. She stepped into the role of Board President in January, and while she’s not new to the job anymore, many in our community may still be getting to know her. Meredith is thoughtful, values-driven, and deeply committed to creating a future where disability doesn’t limit opportunity. She’s a member of the disability community herself, a family member to people with disabilities, and a professional with years of experience leading workforce strategy and inclusion at Fortune 100 companies.

Before she officially took the helm, Meredith shared a powerful message at our National Convention—part reflection, part vision-setting, and a reminder of why The Arc exists in the first place. We’re sharing her message here with you. If you haven’t met Meredith yet, now’s your chance to get to know her.

“Having assumed the role of National Board President for the 2025-2026 term, I am deeply honored by the privilege and responsibility to serve an organization with a rich history of advocacy and a steadfast commitment to protecting and advancing the rights of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. For 75 years, The Arc has been a driving force for inclusion, and I am in awe of the collective impact of our nearly 600 chapters, their leaders and staff, and the communities we serve every day.”

“I imagine that each of us on this journey of advocacy with The Arc has a personal story about when our advocacy began. I can pinpoint the moment when the advocacy flame was lit inside of me. I recall being presented with a diagnosis and a fact sheet from the World Health Organization that accompanied it. The facts remain nearly the same as the ones I read over a decade ago: people with disabilities have poorer health outcomes, experience stigma, discrimination, poverty, and exclusion from education and employment, and more. This information being presented to me as fact—as a certain future—was the moment that lit my fire. Not just as an advocate for one, but as an advocate for all. I became someone who wanted to dedicate as much of my energy and skills as possible toward changing these outcomes.”

“As a person with disabilities (OCD and anxiety disorder), I’m a proud member of the disability community, and I’m grateful that my journey brought me to The Arc.

I’d like to imagine a new set of facts for the disability community.

What if a new fact sheet said:

What if a new fact sheet said:

‘Welcome to your community. You are part of one of the most powerful, connected communities on the planet. Your future is bright. Why? Because people with disabilities are likely to experience inclusive education, employment with robust pay and benefits, personal growth, security, and joy. Oh, and not just that. You’re more likely to help solve big, gnarly problems because this world wasn’t designed with you in mind, and yet you know how to navigate it. You’re more likely to spark innovation with products, services, and spaces—not just for yourself, but for everyone—because YOU bring value and insight to this world. Because you’re a person with a disability, you’re more likely to be a changemaker, both through the work you do and through the insight you bring to others.’

This is the world I wake up to every day trying to help build. And I’m honored to be on the journey with all of you.

So, how will we get there?

I’ve chosen three guiding values for my term as President:

- Leadership by People With Disabilities

We must ensure more people with disabilities, including those with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), are in positions of leadership and influence at a local, state, national, and global level. People with disabilities should not only have a seat at the table, but at the head of it, making decisions, influencing outcomes, and leading. We need systems shaped by lived experience, and we must commit to moving self-determination from theory to practice. - Strategic Focus to Make Meaningful Change

From my time in large Fortune 100 companies, I’ve seen how easily priorities competing for attention can pile up and momentum gets lost. I hope we don’t try to tackle 50 things over the next 2 years. I hope we stay focused where we can make meaningful change, so that 2 years from now, we can point to real, permanent change we made together on a nationwide level. With one voice, one consistent and memorable introduction of who we are and what we do, one aligned strategy and focused set of priorities, I know we can make impact together. - Many Chapters & Constituents of The Arc, Yet One Community

Across nearly 600 chapters, The Arc represents diverse communities, geographies, beliefs, and needs. We will honor those differences, yet try to seek commonality, knowing that we are stronger as one community. The Arc is strongest when we advocate as one voice for and with people with IDD.

Thank you for the chance to share my story, and my vision for our shared work. I’d love to hear your advocacy story, too. You can connect with me on LinkedIn. Together, let’s keep building a world where people with disabilities live with dignity, respect, and opportunity—and where the facts finally reflect that.“

It was a day full of joy, connection, and the kind of belonging that too often feels out of reach. And it all happened because a company chose to step up and demonstrate their commitment to valuing people with disabilities.

It was a day full of joy, connection, and the kind of belonging that too often feels out of reach. And it all happened because a company chose to step up and demonstrate their commitment to valuing people with disabilities. At Great American Ball Park, families got VIP treatment from the moment they arrived. They watched batting practice from the field, met Cincinnati Reds pitcher Brent Suter, and felt welcomed by every staff member they encountered. Before the first pitch, families received gift cards to buy food, thanks to the Reds Community Fund. That small act made it even easier to just enjoy the moment. Then everyone settled into an accessible seating area and watched the Reds take home a win against the Marlins.

At Great American Ball Park, families got VIP treatment from the moment they arrived. They watched batting practice from the field, met Cincinnati Reds pitcher Brent Suter, and felt welcomed by every staff member they encountered. Before the first pitch, families received gift cards to buy food, thanks to the Reds Community Fund. That small act made it even easier to just enjoy the moment. Then everyone settled into an accessible seating area and watched the Reds take home a win against the Marlins. Logan, who has autism and is non-verbal, lit up as he explored the stadium with his parents and sister

Logan, who has autism and is non-verbal, lit up as he explored the stadium with his parents and sister

Marcus Stewart’s smile lights up the room as he talks about his dreams and

Marcus Stewart’s smile lights up the room as he talks about his dreams and  Marcus’s mother, Tawana, has been his fierce advocate from day one. “When he was first diagnosed, his first geneticist told me that he’s not going to amount to much. But I said my son will get every opportunity that’s available,” she recalls. “I made myself present in workshops and other groups of parents of children with Down syndrome. I signed him up for sports. I showed up and was very vocal.” She is frustrated by the lack of opportunities for Marcus in adulthood. “Give him a chance,” she pleads. “He gets up every day without an alarm, makes his own meals, never missed a day of school, takes great care of his nephew and our two dogs. He’s more responsible than most people I know, and he’s capable of so much.” Tawana tears up and Marcus puts his arm around her shoulders.

Marcus’s mother, Tawana, has been his fierce advocate from day one. “When he was first diagnosed, his first geneticist told me that he’s not going to amount to much. But I said my son will get every opportunity that’s available,” she recalls. “I made myself present in workshops and other groups of parents of children with Down syndrome. I signed him up for sports. I showed up and was very vocal.” She is frustrated by the lack of opportunities for Marcus in adulthood. “Give him a chance,” she pleads. “He gets up every day without an alarm, makes his own meals, never missed a day of school, takes great care of his nephew and our two dogs. He’s more responsible than most people I know, and he’s capable of so much.” Tawana tears up and Marcus puts his arm around her shoulders. As we celebrate

As we celebrate

Kris lives with his sister’s family in his hometown of Greely, Colorado, and has been successfully employed for 40 years, currently working full time at the busiest grocery store in town. He is an avid sports fan—Go Bears!—has a busy social life, and because of his gregarious personality he is a bit of a local celebrity, traveling around town on his e-bike. Kris has become very active in civic service—involved with the Chamber of Commerce, volunteering at local nonprofits, and serving in leadership roles at both The Arc of Weld County and on The Arc’s National Council of Self-Advocates.

Kris lives with his sister’s family in his hometown of Greely, Colorado, and has been successfully employed for 40 years, currently working full time at the busiest grocery store in town. He is an avid sports fan—Go Bears!—has a busy social life, and because of his gregarious personality he is a bit of a local celebrity, traveling around town on his e-bike. Kris has become very active in civic service—involved with the Chamber of Commerce, volunteering at local nonprofits, and serving in leadership roles at both The Arc of Weld County and on The Arc’s National Council of Self-Advocates. Roselyn has lived with her mother and received support from The Arc of Greater Indianapolis since 1981. During the week, Roselyn works at Corteva Agriscience through The Arc of Greater Indianapolis’ employment services. She works as part of a team that assists scientists in preparing seedling trays for growing new plants, hosing down trays when experiments are complete, and keeping the greenhouse labs clean. Roselyn is very proud of her work and the independence she has from earning a paycheck. She recently bought a kitchen table set and used her tax check to buy a new washer and dryer.

Roselyn has lived with her mother and received support from The Arc of Greater Indianapolis since 1981. During the week, Roselyn works at Corteva Agriscience through The Arc of Greater Indianapolis’ employment services. She works as part of a team that assists scientists in preparing seedling trays for growing new plants, hosing down trays when experiments are complete, and keeping the greenhouse labs clean. Roselyn is very proud of her work and the independence she has from earning a paycheck. She recently bought a kitchen table set and used her tax check to buy a new washer and dryer.

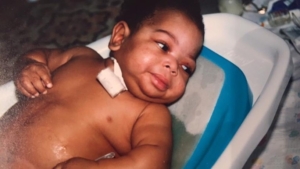

Debbi’s son Josh was born eight weeks early with a grade four brain hemorrhage. As she shares, “He was one of the sickest babies in the neonatal intensive care unit. It started our roller coaster of a journey of having a child with complex medical needs and disabilities.”

Debbi’s son Josh was born eight weeks early with a grade four brain hemorrhage. As she shares, “He was one of the sickest babies in the neonatal intensive care unit. It started our roller coaster of a journey of having a child with complex medical needs and disabilities.” Out of crisis came purpose. Debbi soon immersed her family in The Arc’s chapter support systems, connecting her sons to sibling workshops and herself to a parent networking group. “We still count on those relationships for support today,” added Debbi.

Out of crisis came purpose. Debbi soon immersed her family in The Arc’s chapter support systems, connecting her sons to sibling workshops and herself to a parent networking group. “We still count on those relationships for support today,” added Debbi.

Working with people with disabilities is Lawrence’s long-time passion. He has worked as a direct support professional (DSP) in New York and Texas, both before and after serving in the Army. As a DSP, Lawrence takes pride in the trusted role he has in the lives of people with disabilities. He helps transport people to and from appointments, gives medicine, cooks, cleans, dresses, changes, and feeds people who may not be able to do these things for themselves. He even seeks out specialized training that is needed to support people who have challenging behaviors that may result in injury to themselves and others.

Working with people with disabilities is Lawrence’s long-time passion. He has worked as a direct support professional (DSP) in New York and Texas, both before and after serving in the Army. As a DSP, Lawrence takes pride in the trusted role he has in the lives of people with disabilities. He helps transport people to and from appointments, gives medicine, cooks, cleans, dresses, changes, and feeds people who may not be able to do these things for themselves. He even seeks out specialized training that is needed to support people who have challenging behaviors that may result in injury to themselves and others.