Let’s Talk About Sexual Violence: Addressing Miscommunication, Inexperience, and Bias in Health Care

Written by: Pauline Bosma and James Meadours, Advocates with Disabilities

As people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) who are also survivors of sexual violence, or work with survivors, we face many challenges when trying to get good health care.

We think it’s important to share our stories to help make things better for other people like us. We also want to help health care professionals understand where we are coming from.

Here are some things we have experienced before, or continue to experience:

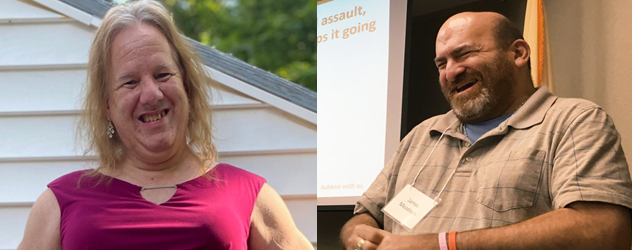

Pictured left: Pauline Bosma, Rainbow Program Coordinator (Rainbow groups are for self-advocates who are members of both the intellectual and developmental disability community and the LGBTQ+ community). Pictured right: James Meadours, Self-Advocate Survivor, Strategic Education Solutions.

James

- I asked staff at my doctor’s office what they would do if someone with IDD came to them for help after being sexually assaulted. They admitted they didn’t know what to do.

- After one of my assaults, I asked for help, but no one knew the right places or resources in the community that could help me.

- I visited my doctor’s office recently about a health care issue, and the nurse who was helping me wouldn’t slow down. She was in a rush. I wasn’t even told my diagnosis. I had to learn about it later at another doctor visit.

Pauline

- There is a lot of miscommunication about how to report sexual violence and health care professionals not knowing what to do or not do.

- As a transgender individual with IDD, I see and experience a lot of stigmas. Health care professionals think I’m not sexual because I have an IDD. They’ve told others they can’t be gay because they have a disability. Some health care professionals don’t feel comfortable using our pronouns.

- Health care professionals often don’t look at or talk to their patients with IDD but will talk to their support person, parent, or other caregiver instead.

- It’s really hard to find a therapist who will talk about transgender issues and who takes Medicaid. Transportation is also hard to find. It’s hard to find someone near me. It feels like I’m going through this all by myself.

We believe change can happen when health care professionals get to know us as human beings and listen to what we need.

Here are some ideas that doctors, nurses, and others can keep in mind to help communicate better and have more authentic connections and conversations with patients with IDD:

- Listen and believe us! When people with disabilities have just experienced the most significant trauma of their lives, it is incredibly painful and lays additional trauma on top of the original trauma if we are not listened to, heard, and believed. The system that is set up to help us ends up re-victimizing us.

- Have an open mind and be sensitive to us no matter what our disability or sexuality is. Please use our correct pronouns. It helps us feel “seen.”

- As frontline health care workers, please learn about resources and agencies in the community that can help survivors with IDD and share those with us. We need to know how to find therapists who have experience working with survivors with IDD, including those in the LGBTQ+ community. We need to find support groups that can include us, even if we need accommodations to be included.

- Don’t make assumptions about us. People with IDD are sexual, just like many people without disabilities! We may be straight, gay, or transgender. There’s a lot of diversity in the disability community.

- Keep educating yourself about this silent epidemic! Learn about the data. People with IDD are more likely to experience sexual violence. In fact, they experience it at seven times the rate compared to people without disabilities.

- Some of us may be afraid to speak out about sexual violence if it reveals our sexual orientation. We may not be ready to come out because we are afraid and lack support. Help us feel safe.

- Normalize conversations with patients about sexuality, especially with those who have IDD. We want to talk about things like what is sexual violence; how to prevent sexual violence; and where to get help from people or agencies that understand the IDD community.

- Give us information in plain language that is easy for us to understand. Use pictures so that we can understand if we have trouble reading something.

- Ask if your office can get training on this topic from your local disability advocacy group, self-advocacy group, or LGBTQ+ advocacy community. We want to give the training ourselves because this means no one is putting words in our mouths. It also helps health care providers relate to us.

The Talk About Sexual Violence project trains health care providers about ways to ensure their appointments with survivors with IDD are accessible. We need your help to educate as many health care providers as possible about how important it is to use a trauma-informed care approach.

Taking action is important. Please share this blog and the Talk About Sexual Violence training tools with others, and sign the pledge to prevent sexual violence. YOU can be the change!

Barbara’s son Jake is a medically complex young adult living at home with his parents. Jake relies on Medicaid to provide the services he needs to be medically safe and supported at home, including continuous skilled nursing and personal care assistance (PCA).

Barbara’s son Jake is a medically complex young adult living at home with his parents. Jake relies on Medicaid to provide the services he needs to be medically safe and supported at home, including continuous skilled nursing and personal care assistance (PCA).

Cassie is a mother, former educator, and co-founder of

Cassie is a mother, former educator, and co-founder of  Between August and December of his first-grade year, Cassie recorded that six-year-old Kai was sent for “time away” around 100 times, much of which took place in a seclusion room.

Between August and December of his first-grade year, Cassie recorded that six-year-old Kai was sent for “time away” around 100 times, much of which took place in a seclusion room.

When her seven-year-old son was in first grade, Michigan mom Amanda got an unexpected call from the new school principal. Her son, who has autism, had kicked the principal, and Amanda was being asked to keep her son home from school the next day.

When her seven-year-old son was in first grade, Michigan mom Amanda got an unexpected call from the new school principal. Her son, who has autism, had kicked the principal, and Amanda was being asked to keep her son home from school the next day.

Fifteen years ago, within days of being born, we learned that our son had Down syndrome. This sent us into a flurry of information gathering, advocacy, and more.

Fifteen years ago, within days of being born, we learned that our son had Down syndrome. This sent us into a flurry of information gathering, advocacy, and more.