The following blog post was originally published by the Legal Defense Fund and is reposted here with permission.

In San Antonio, Texas, community members and advocates gathered outside of the federal courthouse on October 2, 2023 with emblazoned signs in hand, shouting spirited chants. As a trial was underway inside, echoes of their rallying calls for voting rights reverberated through the city streets. Candace Wicks, a retired teacher who traveled 300 miles from Dallas to show her support, shared her story to the burgeoning crowd with a mixture of frustration and determination. Wicks, a Texas native who has disabilities, has remained unwavering in her commitment to voting her entire life—yet since the state’s restrictive voting law S.B. 1 was passed in 2021, she has faced significant barriers participating in the electoral process.

In last year’s midterm elections, Wicks encountered an array of obstacles in attempting to exercise her right to vote. Wicks, whose legs and nine fingers are amputated and does not have a consistent signature, had her ballot denied because of a new signature verification process that S.B. 1 requires. Wicks also cited the law’s curbside voting restrictions and additional, limiting requirements on voter assistance as detrimental requirements for disabled voters.

“People with disabilities already face numerous barriers and discrimination in their daily lives,” Wicks emphasized in her speech. “Voting should not be added to that list. Our democracy is only strong when it represents all its citizens.”

Wicks is a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc., a historically Black service-based sorority that is named a co-plaintiff in the lawsuit challenging the voter suppression law. Lupe v. Abbott, composed of five lawsuits including Houston Area Urban League v. Abbott, argues that S.B. 1 is discriminatory, imposing undue barriers on voters to participate in elections, especially voters of color and voters with disabilities.

Plaintiffs including the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc., Houston Area Urban League, and The Arc of Texas argue that S.B. 1 violates the United States Constitution and Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by targeting and burdening methods and means of voting, like drive-thru voting and 24-hour voting, that are largely used by voters of color. Plaintiffs also argue the law violates the Americans with Disabilities Act, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and Section 208 of the Voting Rights Act by inflicting barriers to voting on voters with disabilities by imposing restrictions on voter assistance and making it harder to vote by mail, denying them full and equal opportunities to participate in the state’s voting processes.

The six-week trial began on Sept. 11. In that time, witnesses took the stand to provide testimony about their own experiences attempting to access the ballot box. Since being enacted in 2021, the law has already had grave consequences, rendering many residents unable to vote and making the process of voting far more onerous and burdensome, resulting in significantly longer voting times and physical pain for some voters with disabilities. Some who attempted to vote had their ballots denied.

For the several millions of Texans the law’s provisions impacts, including an estimated 3-5 million voting-eligible Texans with disabilities, the reversal of this legislation is dire for our nation’s democracy. All Texas voters, regardless of their identities or backgrounds, deserve to be counted—and their voices heard.

“People with disabilities already face numerous barriers and discrimination in their daily lives. Voting should not be added to that list. Our democracy is only strong when it represents all its citizens.” – Candace Wicks, Retired Dallas Teacher and Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Member

Leading a Fight Against Voter Suppression in Texas

In the fight for an inclusive democracy in Texas, civil rights organizations are working together to fight S.B. 1 and bring forth justice.

“Our challenge to S.B. 1 highlights that voter suppression is a disability rights issue and that the fight against voter suppression lies at the intersection of disability rights and racial justice,” said Amir Badat, LDF Voting Special Counsel, who manages LDF’s Voting Rights Defender and Prepared to Vote projects. “There are millions of Texans who have a disability. Voters with disabilities are entitled to equal access to the ballot box. S.B. 1 undermines that right by increasing the already significant burdens that voters with disabilities must overcome to cast their votes and have them counted. By bringing this case, our plaintiffs who have disabilities are telling the world that their voices matter and must be heard.”

The lawsuit challenges multiple provisions in S.B. 1 that, by imposing undue limitations on voting, disproportionately impact voters of color and voters with disabilities.

Voting restrictions imposed by S.B. 1 include:

- Limitations on early voting hours.

- A ban on 24-hour voting.

- A ban on drive-thru voting.

- Limitations on the distribution of mail-in ballot applications.

- Limitations and possible penalties for voter assistants, including criminal felonies.

- Expansion of the authority of partisan poll watchers.

- Criminal penalties against poll workers seeking to maintain order at the polling place.

“There are millions of Texans who have a disability. Voters with disabilities are entitled to equal access to the ballot box. By bringing this case, our plaintiffs who have disabilities are telling the world that their voices matter and must be heard.” – Amir Badat, LDF Voting Rights Special Counsel and Voting Rights Defender and Prepared to Vote Projects Manager

While the Texas state legislature makes claims of voter fraud, a myth long debunked by experts and advocates alike, the passage of the law is antithetical to true integrity and democracy—placing significant hardship on voters who have historically been counted out.

Texas is one of at least 18 other states that have passed voter suppression laws in direct response to voters from marginalized communities, including voters of color and voters with disabilities, making their voices heard in record numbers during the 2020 elections. Within Texas’s long history of voter suppression is a painful reality—the intentional suppression, prevention, and displacement of minority votes.

“People with disabilities have the fundamental right to vote and participate in our democracy, but this right has too often been denied,” said Shira Wakschlag, Senior Director of Legal Advocacy and General Counsel for The Arc of the United States. “S.B. 1 disenfranchises voters with disabilities by making it harder to vote by mail and receive the assistance they need to vote, and it denies people with disabilities equal access to voting in violation of the law.”

Voting Rights Is a Disability Rights Issue

Texas Voters With Disabilities Share Their Stories

Four voters with disabilities who served as witnesses in the trial discussed how S.B. 1 impacted their ability to vote, and what they hope to see from the state’s voting policies moving forward.

Some quotes have been condensed for clarity.

TERI SALTZMAN, Travis County resident and member of The Arc of Texas and REVUP Texas

Teri Saltzman is blind and faced a myriad of barriers to voting by mail in the midterm primary elections. Her mail ballot was rejected multiple times because the ID numbers she provided didn’t match her voter registration record. She could not cure her ballot online because the state’s website is inaccessible to blind voters. After four attempts at curing her ballot, she was notified that her ballot did not count. Saltzman’s ballot was again denied in November 2022.

Teri Saltzman is blind and faced a myriad of barriers to voting by mail in the midterm primary elections. Her mail ballot was rejected multiple times because the ID numbers she provided didn’t match her voter registration record. She could not cure her ballot online because the state’s website is inaccessible to blind voters. After four attempts at curing her ballot, she was notified that her ballot did not count. Saltzman’s ballot was again denied in November 2022.

“I registered to vote by mail based on my disability and I have always done this successfully in the past. When S.B. 1 passed, it was the first time in my life I had difficulty voting due to its ID requirements and burdens. I never had this amount of challenges voting. I was never unsure if my vote counted.

“S.B. 1 has meant a reversal of rights for this community. Disability rights has everything to do with voting rights. What they’re voting for—transportation, education, housing, all those things—are linked to their independence as a person with a disability. I will always vote. But when I look at the ballot [sitting here on my table], I look at it with trepidation. [Voting] is something that I love…it’s something that is important in my family. But now, after a whole year of fighting to exercise my right to vote, I have this hesitancy that I never had before. I’m mad that it is there. But I will still vote. I’m concerned about voters who are already hesitant—who if they come across these barriers, might be prevented from doing so at all.”

JODI LYDIA NUNEZ LANDRY, Harris County resident and member of The Arc of Texas and REVUP Texas

Jodi Lydia Nunez Landry has muscular dystrophy and has encountered significant barriers since S.B. 1 was enacted. Landry prefers to vote in person but is afraid to get voting assistance from her partner due to risk of criminal prosecution S.B. 1 has imposed on voter assistance. She explains that her disability is degenerative and that as a result, she will require even more assistance over time.

Jodi Lydia Nunez Landry has muscular dystrophy and has encountered significant barriers since S.B. 1 was enacted. Landry prefers to vote in person but is afraid to get voting assistance from her partner due to risk of criminal prosecution S.B. 1 has imposed on voter assistance. She explains that her disability is degenerative and that as a result, she will require even more assistance over time.

“I think voting is fundamental to our democracy. The people that we elect are the ones that hold the power and represent us and make policies that affect our entire lives. [Elected officials determine] whether disabled people can vote, get out of their homes or have employment and educational opportunities, whether people are institutionalized or whether they’re able to enjoy basic human rights.

“S.B. 1 has had a very profoundly negative impact on our community. My condition has progressed, and I’ve increasingly run into more obstacles [since S.B. 1 was enacted]. I completely rely on my partner, who is also my personal attendant, to assist me with things.

“I think it really boils down to whether people believe that disabled people or any people from marginalized groups are deserving of the full benefits of democracy. We’re all interconnected. Disabled people come from every walk of life. And I think that’s the beauty of, at least, the promise of democracy—we all get to enjoy the same basic human rights and privileges as everyone else.”

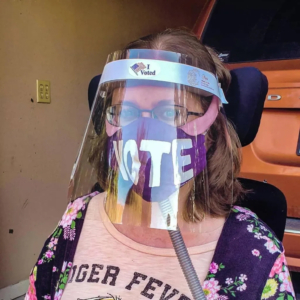

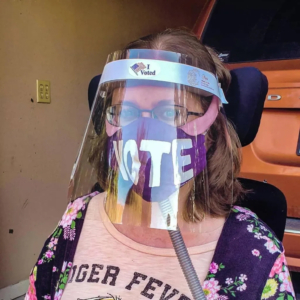

LAURA HALVORSON, Bexar County resident and member of The Arc of Texas and REVUP Texas

Laura Halvorson has muscular dystrophy and chronic neuromuscular respiratory failure. Halvorson relies on a power machine, a breathing machine, and personal care attendants for a majority of her care. Halvorson has encountered significant barriers to voting since S.B. 1 was enacted. Unlike previous years, Halvorson could not get assistance to vote by mail. Her personal care attendant, who is a green card holder, was not willing to assist Halvorson with her mail ballot during the March 2022 primary due to the threat of criminal liability and the potential impact on her legal status. As a result, Halvorson had no choice but to open and mark the ballot herself—a process which took her multiple attempts and was significantly longer and more arduous than if she had been assisted. As a result of these challenges, Halvorson chose to vote in person in the November 2022 election — a process which again took her significantly longer and was far more difficult because she did not receive any assistance.

Laura Halvorson has muscular dystrophy and chronic neuromuscular respiratory failure. Halvorson relies on a power machine, a breathing machine, and personal care attendants for a majority of her care. Halvorson has encountered significant barriers to voting since S.B. 1 was enacted. Unlike previous years, Halvorson could not get assistance to vote by mail. Her personal care attendant, who is a green card holder, was not willing to assist Halvorson with her mail ballot during the March 2022 primary due to the threat of criminal liability and the potential impact on her legal status. As a result, Halvorson had no choice but to open and mark the ballot herself—a process which took her multiple attempts and was significantly longer and more arduous than if she had been assisted. As a result of these challenges, Halvorson chose to vote in person in the November 2022 election — a process which again took her significantly longer and was far more difficult because she did not receive any assistance.

“This new voting law makes it even harder for people to vote and [is] a huge act of voter suppression in a state with already one of lowest voter turnouts in the country. Once S.B. 1 was enacted and I experienced new barriers in voting, I felt it was important to share my story.

“I hope voting becomes easier and more accessible for people with disabilities in Texas, but I do not see how that could be possible with S.B. 1 still in place.

“It is important for people with disabilities and others in our lives to let our voices and issues be heard by politicians and reflected in their platforms to show the power of the disability vote. About one in four Americans has a disability, and many acquire a disability through the aging process and now also through long Covid, so disability issues affect many people and/or their loved ones in the voting process and access.”

JENNIFER MILLER, Travis County resident and member of The Arc of Texas

Jennifer Miller is the mother of an adult daughter, Danielle, who has autism. Miller regularly assists her daughter to vote, yet has encountered significant barriers in doing so since S.B. 1 was enacted.

“I care very much about this country as a long-time resident of Texas, and I care very much about my daughter. She has learned civic responsibility, and as a person with a disability, voting really makes a difference for her and her community. As a supportive parent, I want to let my daughter have the best life she can and be independent. One of those factors is her being able to exercise her right to vote.

“Voting is a constitutional right. If [S.B. 1] continues, a lot of people might give up and not vote. And that’s not right, because their voices need to be heard. Voting is everything to marginalized communities. The [Americans with Disabilities Act] isn’t that old, and we’re still fighting for rights.”

Being Heard, Being Counted: Making Democracy Inclusive for All

Closing arguments in the trial will be heard in February 2024. As voters await the trial’s results, one thing is certain — every voter has a voice that should be heard through the electoral process, and all people, regardless of their identity or background, are entitled to fully participate in our nation’s democracy. Texas’s electoral process should be accessible to all. A true democracy should be more than an ideal—it should be fully enforced through protections for all voters, including those who have historically had their ballots left out.

The killing of Ryan Gainer, a Black autistic teen, is a devastating injustice. Too many people with disabilities, especially those from marginalized communities, cannot access the crisis intervention services they need. In the face of Ryan’s mental health crisis, his family called 911 for help. Instead of receiving the care he needed from a competent professional, he was killed. Because of the tragedy of Ryan’s death and the death of others before him, The Arc’s National Center on Criminal Justice & Disability is working to reform our public safety practices across the country. This center offers comprehensive training to improve crisis response for people like Ryan. Our hearts go out to the Gainer family and all those who loved Ryan. We pledge to continue to keep working for a just, equitable world for all people with disabilities.

The killing of Ryan Gainer, a Black autistic teen, is a devastating injustice. Too many people with disabilities, especially those from marginalized communities, cannot access the crisis intervention services they need. In the face of Ryan’s mental health crisis, his family called 911 for help. Instead of receiving the care he needed from a competent professional, he was killed. Because of the tragedy of Ryan’s death and the death of others before him, The Arc’s National Center on Criminal Justice & Disability is working to reform our public safety practices across the country. This center offers comprehensive training to improve crisis response for people like Ryan. Our hearts go out to the Gainer family and all those who loved Ryan. We pledge to continue to keep working for a just, equitable world for all people with disabilities.

Teri Saltzman is blind and faced a myriad of barriers to voting by mail in the midterm primary elections. Her mail ballot was rejected multiple times because the ID numbers she provided didn’t match her voter registration record. She could not cure her ballot online because the state’s website is inaccessible to blind voters. After four attempts at curing her ballot, she was notified that her ballot did not count. Saltzman’s ballot was again denied in November 2022.

Teri Saltzman is blind and faced a myriad of barriers to voting by mail in the midterm primary elections. Her mail ballot was rejected multiple times because the ID numbers she provided didn’t match her voter registration record. She could not cure her ballot online because the state’s website is inaccessible to blind voters. After four attempts at curing her ballot, she was notified that her ballot did not count. Saltzman’s ballot was again denied in November 2022. Jodi Lydia Nunez Landry has muscular dystrophy and has encountered significant barriers since S.B. 1 was enacted. Landry prefers to vote in person but is afraid to get voting assistance from her partner due to risk of criminal prosecution S.B. 1 has imposed on voter assistance. She explains that her disability is degenerative and that as a result, she will require even more assistance over time.

Jodi Lydia Nunez Landry has muscular dystrophy and has encountered significant barriers since S.B. 1 was enacted. Landry prefers to vote in person but is afraid to get voting assistance from her partner due to risk of criminal prosecution S.B. 1 has imposed on voter assistance. She explains that her disability is degenerative and that as a result, she will require even more assistance over time. Laura Halvorson has muscular dystrophy and chronic neuromuscular respiratory failure. Halvorson relies on a power machine, a breathing machine, and personal care attendants for a majority of her care. Halvorson has encountered significant barriers to voting since S.B. 1 was enacted. Unlike previous years, Halvorson could not get assistance to vote by mail. Her personal care attendant, who is a green card holder, was not willing to assist Halvorson with her mail ballot during the March 2022 primary due to the threat of criminal liability and the potential impact on her legal status. As a result, Halvorson had no choice but to open and mark the ballot herself—a process which took her multiple attempts and was significantly longer and more arduous than if she had been assisted. As a result of these challenges, Halvorson chose to vote in person in the November 2022 election — a process which again took her significantly longer and was far more difficult because she did not receive any assistance.

Laura Halvorson has muscular dystrophy and chronic neuromuscular respiratory failure. Halvorson relies on a power machine, a breathing machine, and personal care attendants for a majority of her care. Halvorson has encountered significant barriers to voting since S.B. 1 was enacted. Unlike previous years, Halvorson could not get assistance to vote by mail. Her personal care attendant, who is a green card holder, was not willing to assist Halvorson with her mail ballot during the March 2022 primary due to the threat of criminal liability and the potential impact on her legal status. As a result, Halvorson had no choice but to open and mark the ballot herself—a process which took her multiple attempts and was significantly longer and more arduous than if she had been assisted. As a result of these challenges, Halvorson chose to vote in person in the November 2022 election — a process which again took her significantly longer and was far more difficult because she did not receive any assistance.